The last three sets of local elections in London have seen Labour forging ahead in the capital despite losing the last four general elections, and London is now routinely described as a “Labour city”. As the 5 May borough votes approach, has London reached “peak Labour” or is there potential for the party to make further gains?

Brexit and The Great Realignment

The conventional explanation for Labour’s increasing dominance in London is the “Great Realignment” theory of British politics. Voting used to be strongly connected with social class, but this relationship has broken down in the last 40 years. Over the last decade, voting has also become less correlated with views on economic left/right issues (for example whether you agree that the government should redistribute income to those who are worse off). Views on questions of “values” or “culture” (for example on the death penalty or immigration) have become more important.

Brexit was a symptom of this shift with voting in the referendum strongly linked to “values”. But the Brexit vote also became a catalyst for a change in party political voting. In the last few elections the Conservatives have picked up authoritarian voters – even when those voters might have economically left wing views – and Labour has attracted more liberal votes. This matters in London because liberal values are more likely to be held by people who are highly educated and young, and the capital has a disproportionate number of both groups.

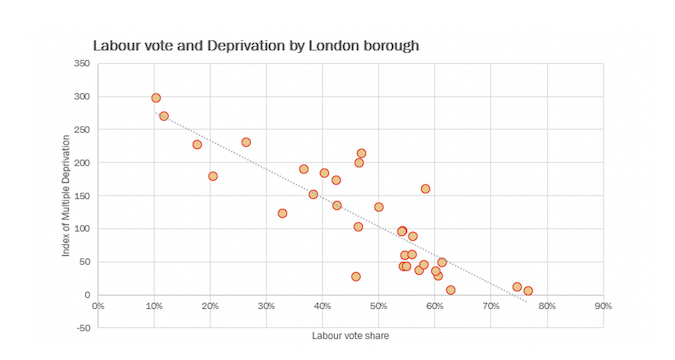

But economics does continue to matter when it comes to voting. Labour still tends to represent the most deprived parts of the country, including in London, where there is a strong link between between deprivation in London boroughs (as measured by the Index of Multiple Deprivation) and Labour vote share.

There is a (slightly weaker) link between lack of deprivation and high Tory vote share. The Conservatives tend to do well in suburban areas such as Bromley, where wages and house prices are lower than those in Central London, but which also have fewer areas of deprivation.

The relationship between party vote and EU referendum vote is much looser. Labour has retained its grip on deprived boroughs, even when they voted Leave. Equally, boroughs with low levels of deprivation have stayed solidly Tory despite voting Remain.

But Brexit has caused changes in voting patterns in London. In the London Assembly elections in 2021 the Tories did better in boroughs with high Leave votes, but the places where they made the most gains were either already safe Tory boroughs such as Bexley or boroughs like Barking & Dagenham where Labour is too dominant for the shift to have much of an impact.

On the Labour side, there were only eight boroughs where the party improved its vote share between 2016 and 2021, of which seven had voted Remain – though worryingly for the Conservatives they included the key Labour target councils of Westminster, Wandsworth and Barnet.

The debate over the referendum is much less ferocious than it was three years ago. But although the strength of “Remainer” and “Leaver” identities have faded slightly (particularly on the Leave side), they are still stronger than attachments to political parties and still have the potential to impact voting choices. This is particularly true since the last council elections in London were in 2018 before Brexit became so divisive during the dramas of 2019.

Who are the swing voters?

One of the effects of the realignment in politics is that voters have become more volatile, more likely to switch parties between elections and more reactive to events such as the Partygate scandals. Those who switched from voting Labour in the 2017 General Election to Conservative in 2019 tend to be quite economically left leaning, though most also voted Leave in the referendum.

Although overall, London voted to Remain it is worth remembering that two in five Londoners were Leavers. More of these switchers still identify with Labour rather than with the Tories, suggesting that many of them only “lent” their vote to the Conservatives in 2019 and potentially could swing back to Labour.

But national opinion polls show that many of these voters have moved to “Don’t Know” rather than switching directly to another party, and in local elections with relatively low turnout, it may be the case that many of them do not bother to vote at all.

Another set of swing voters are those with socially liberal views (who are therefore at odds with the current Tory government), but who are economically right-leaning. Many of them voted Remain in the referendum, but stuck with the Tories in 2019 because of the fear of a Corbyn-led Labour government.

The Liberal Democrats are generally best placed to pick up these voters, as their stunning victory in the Chesham & Amersham by-election last year demonstrated and in wards where they are competitive they are likely to do well. However, the only three boroughs where the Lib Dems have high enough vote share to be in serious contention for control of the council are ones which they already hold.

There is also evidence that some unhappy socially liberal Tory voters in London might also consider voting Labour. In 2021, the places where Labour improved on its 2016 performance were boroughs with middling levels of deprivation and which voted Remain, for example Labour came unexpectedly close in the Tory-held London Assembly seat of West Central (comprising Kensington & Chelsea, Westminster and Hammersmith & Fulham).

The third set of voters who might prove significant are left-wing current Labour voters who were enthusiastic about Corbyn’s leadership of the party, but less so about Starmer’s and who might defect to the Greens. Since Corbyn’s departure, the Greens have seen a resurgence in national polling and did well in the 2021 mayoral and Assembly elections. Although at general elections the Green vote invariably gets squeezed, voters often feel less worried about casting votes for smaller parties in local elections, and this could prove damaging for Labour’s chances.

Who will win in London?

At the last set of London council elections in 2018, the Conservatives were around four per cent ahead in the national opinion polls, currently Labour is on average ahead by a similar margin. Taken together with the structural moves towards Labour in London, it is hard to imagine that the party will not improve its position in terms of vote share and number of councillors.

But whether this translates into control of more councils will depend in part on local circumstances (for instance, Labour could lose control of Croydon because of the council’s financial problems), and partly on the behaviour of volatile and unpredictable groups of swing voters, who react strongly to current events. Four weeks can be a long time in politics.

On London is a small but influential website which strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. Become a supporter for £5 a month or £50 a year and receive an action-packed weekly newsletter and free entry to online events. Details here.