The rise of cycling activism has become a conspicuous feature of London’s clogged and seething transport landscape in recent years. It has spawned a kind of transport identity politics, strident in its assertion of itself, defining its values as opposed to an oppressive status quo. And its influence is not in question.

Confident, articulate and untroubled by doubt about the virtues of their cause, the evangelists of pedal power have long shown themselves accomplished at attracting friendly publicity, piling on social media pressure and even securing roles forming mayoral policy, apparently regardless of their qualifications for such tasks. In these respects their success has been outstanding. It is, though, far less clear if the victories they have won are producing the promised results.

A recent taster of the latest Travel In London report, Transport For London’s annual compendium of stats and trends, said that the growth of cycling in London in recent years seems to have “stalled”. The report, the eleventh of its kind, has now been published in full and more detail about cycling’s progress in the city can be found.

Some of the data does not break new ground. In 2017, cycling accounted for a tiny two per cent of both complete trips from A to B and individual journey stages in London, just as it has since 2005, when it doubled by both measures compared with the previous eight years. During the same 20 year period – 1997-2017 – public transport’s modal share has risen from 26 per cent to 37 per cent, while that of private transport has fallen from 48 per cent to 36 per cent. This big turnaround dwarfs both the significance and the expansion of cycling during that time.

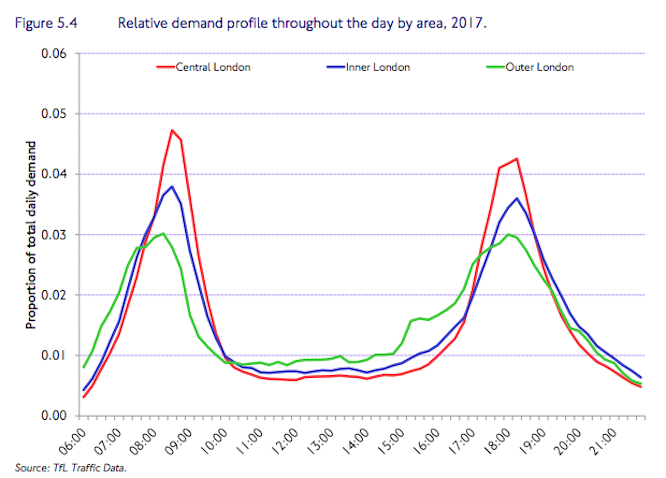

Further figures indicate when and where Londoners cycle and which groups of Londoners are doing it. Central London sees more than double the number of people cycling per day than Inner London with Outer London lagging far behind, though those excursions in the centre – which accounts for just two per cent of Greater London as a whole – are on average much shorter. What all parts of the city have in common is a concentration of cycling around the morning and evening travel peak periods with a huge drop in between.

Demographic trends are striking too. The number of women who cycle at least once a year has increased slightly over time, but they are still a minority and a smaller one among regular cycling commuters. The ethnic profile of cyclists remains predominantly white, with only about one in four Londoners who cycle at least once a year being from BAME groups compared with 37 per cent of the population as a whole. This has changed little since 2010, producing what the report calls “a rather static picture”.

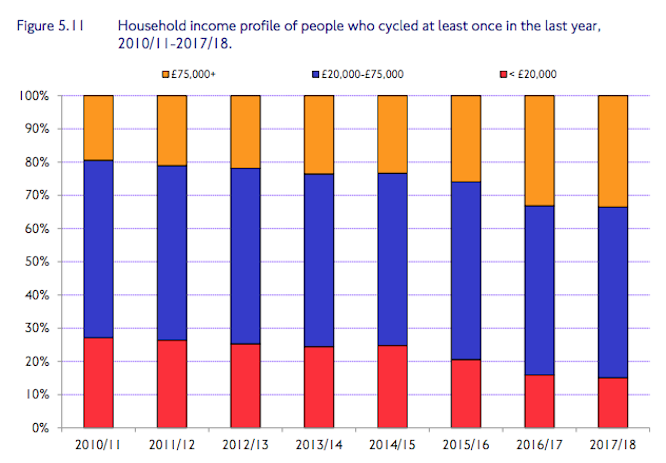

Most people who cycle at least once a year are in employment, and that percentage has increased pretty steadily. So has the percentage from households with incomes of more than £75,000 a year – up successively from 20 per cent in 2010/11 to around 35 per cent in 2017/18, suggesting, says the report, that cycling is increasingly “a lifestyle choice” for the more affluent.

Further survey data indicate that claims that the new infrastructure would, of itself, produce a larger and broader quantity of cycling participation – “build it and they will come” – are not being borne out. Two-thirds of Londoners who don’t cycle regularly say they are unlikely to do so in the future, part of a picture that has changed little over time. But one attitude that has changed, and markedly, in recent years has been the percentage of Londoners who agree with the statement that “cycling is not for people like me”. This has risen from 36 per cent in 2013 to nearly 50 per cent in 2017. This, the report says, suggests that cycling has an image problem. It is “perceived as an exclusive mode or one that is only accessible to certain demographic groups”.

All of the above is not meant to be happening. When Boris Johnson published his Vision for Cycling in 2013, its several good objectives included more women and BAME Londoners cycling and, generally, “more cyclists of all social backgrounds, without which truly mass participation can never come”. The Vision ushered in a concerted period of investment in new cycling infrastructure – the suburban Mini-Hollands, the Quietways and the Superhighways – which, Johnson claimed, would bring about the increases in numbers and variety of cyclist he desired.

Cycling activists too have subscribed firmly to this view, some of them responding with chortling ridicule to any argument that barriers to broader cycling participation cannot be broken down by re-designing streets alone.

But what story do TfL’s new figures tell? Far from being one in which solid progress towards “mass participation” is being made thanks to a growing cyclist demographic that increasingly resembles London’s human and economic diversity, we have cycling growth levelling off and a cycling population still dominated by commuting white males, of whom an increasing percentage are at the upper end of the wage scale. And while the report also says that some segregated lanes and other innovations are bringing more cycling to the streets affected than was there before, that is not the same thing as the “cycle revolution” that was foretold. The overall picture is that such growth as has occurred is due to people who cycled anyway doing it more.

Under Sadiq Khan, cycling policy and its implementation have improved, thanks largely to his appointment of a cycling advisor with a far more mature approach than his predecessor. This has been evident in several ways, including his recognition of obstacles to a flourishing and all-embracing London cycling culture that have little if anything to do with road infrastructure – something TfL acknowledges too.

But those obstacles seem to be getting larger. The more special provision that has been made for cycling and the higher cycling’s public profile has become, the larger has grown that percentage of Londoners surveyed who say that cycling is not for people like them. For cycling activists of a certain kind, that fact above all should give cause for self-reflection. They think they know the route to making London truly a cycling city. But maybe they’ve become part of a roadblock.

Read the whole of TfL’s Travel in London Report 11 via here.

As a recent (white, retirement age, upper income, male) convert to cycling I am truly converted – it’s a much better way to get around, at least in the immediate locality. I don’t commute in the normal sense and I was struck by, and remain affected by, Chris Boardman’s video about Utrecht https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DDLb6biq39A

There is huge resistance in my part of London to ‘Cycle Superhighway 9’ which is shockingly unfortunately named and creates visions of lycra-clad commuters zooming up pavements at 25mph. This is not what it’s for. It should be (and I think is) aimed at pootlers like me who want to go to the shops/dentist/school/pub in ordinary clothes.

There are other bizarre and annoying features of cycling which reflect that ib this country it remains an activity dominated by enthusiasts rather than people who just want cheap, simple transport.

The way that gears work is Heath-Robinson and in my experience extremely unreliable. I have barely had a week where all gears are working properly.

Why are bikes sold without lights? It’s a pain in the neck putting them on and taking them off yet if you leave even Poundland ones on the bike they get nicked in no time. Try buying a car without lights fitted (also I have had a car for 50 years and never once had a light nicked 🙂

[…] and bus use alike. None of this is good for transport budgets, with fares revenues hit and questions raised about value for public money. There is considerable alarm about the future of London’s bus […]