With the High Court giving it the green light, Sadiq Khan’s expansion of the capital’s ultra-low emission zone (ULEZ) to the whole of Greater London looks sure to go ahead from 29 August. Soon afterwards, opposition to it, already less than universal, will start to fade. Resistance to it will continue to be loud, but increasingly unrepresentative.

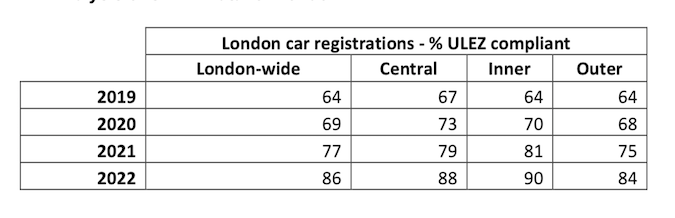

That is because only a very small minority of Londoners will be directly affected by the expansion. According to the 2021 Census, 42 per cent of London households don’t own or have access to a motor vehicle at all. And when we look at the 58 per cent that do, data gathered by the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SSMT) show that, in 2022, 86 per cent of cars registered in Greater London complied with ULEZ anti-pollution standards.

That was an increase of nine per cent compared with 2021. If we assume the same upward trend has continued during this year, the ULEZ compliance rate will already be above 90 per cent – perhaps comfortably so, if the imminence of the expansion has accelerated the rate at which people are getting rid of non-compliant cars.

If so, it means only about five per cent of London households will end up having to pay the £12.50 daily charge because their vehicles fall into the most-polluting categories. A chart from Transport for London’s explanatory note about the SSMT data is shown below.

For candidates for London Mayor, the electoral implications of this are significant. It means that once the expansion begins the vast majority of Londoners who own cars and drive them in the outer London areas the ULEZ will have expanded to will feel no direct effect (except, perhaps, the benefit of a small reduction in congestion as remaining owners of non-compliant vehicles choose not to drive them).

That means the potential political advantage to the Conservative candidate Susan Hall, who has been claiming that Sadiq Khan is forcing the expansion on an electorate that doesn’t want it, will shrink and keep shrinking. Yes, there are caveats: some new owners of compliant vehicles will still resent having had to upgrade; some voters will oppose the expansion because they simply think it’s wrong or believe it is hurting them indirectly; the compliance rate among van-owners, typically small business people, is far lower (although the number of vans is far smaller than the number of cars); it will continue to be an issue in the election campaign, with Hall citing it as but one example of Khan being tin-eared and arrogant.

Even so, the ULEZ expansion is about to become a diminishing electoral asset for Hall, as motor-owning Londoners learn first hand that, contrary to what many may have been led to fear, they are, in fact, not being charged £12.50 a day to get round outer London’s roads. Of those who are, some will be non-voters. Some, perhaps most, will be Tory voters anyway. What will Hall do next?

We already know the answer.

Earlier this month, the headline of a right wing website proclaimed: “Sadiq Turbo-Charges Pay-Per-Mile Plot”. A transport minister had told the Commons that he had been told by Deputy Mayor for Transport Seb Dance and by TfL’s top finance official that Khan had asked them to examine the “technicalities” of introducing road-user charges for all vehicles throughout London in the future. And on Friday, the very day of the High Court ruling, one of Hall’s fellow Tory AMs warned Daily Express readers that plans for such a pay-per-mile system are already being worked on by a special TfL group.

Does such activity merit the description “plot”? Will such a pay-per-mile road-user pricing scheme be introduced by Sadiq Khan should he be re-elected next May?

Well, for a “plot”, activity in this area hasn’t been terribly secret. Khan’s statutory transport strategy, published way back in March 2018, said he would keep the effectiveness of London’s various road user charging schemes under review and “investigate proposals for the next generation of road user charging systems”. These, the strategy said, could potentially replace all the existing ones, including the Congestion Charge and the ULEZ, using “more sophisticated technology” than was available. Proposal 21 of the strategy stated:

“The Mayor will consider the appropriate technology for any future schemes, and the potential for a future scheme that reflects distance, time, emissions, road danger and other factors in an integrated way. TfL will develop the design, operation and technical elements of these proposals in consultation with road users and stakeholders.”

The relevant section of the transport strategy is reproduced below.

The “plot”, then, has been being hatched in plain sight for three-and-a-half years. And versions of such a “plot” have been around in City Hall for much longer.

In May 2009, in advance of published his own transport strategy, Mayor Boris Johnson wrote: “In the future, wider road user charging may be explored in the context of a national scheme and charging in town centres may also be considered.”

Johnson’s strategy itself, published in October 2009, while recommitting to removing Ken Livingstone’s western extension to it, said Johnson would keep the central London Congestion Charge zone “under review” and would consider other measures to control congestion, “such as parking charges or road user charging schemes”. A Johnson idea of charging motorists around £1 a mile to use London’s busiest roads received a friendly response from the Evening Standard. Such ideas were discussed under Livingstone too.

Khan’s “plot” has also been a rather conspicuous element of TfL’s public consultation about the latest ULEZ expansion, which began last May. This additionally invited Londoners to share their thoughts about what any “future road user charging scheme” should be like. Again, as plots go, not terribly secret.

The possibility of such a system coming to pass has also been discussed several times at public meetings at City Hall. Khan’s remarks about it have been consistent: there is no plan to introduce such a system, not least because we don’t yet know how to do it in the way described in his transport strategy.

Could that change in time for Khan to indeed have the option of bringing in what some call “smart” road user pricing across the whole of the capital in the near future?

Perhaps we shouldn’t hold our breath. Last June, On London supporters heard from a trio of experts that the technology required exists but that there are currently no models for the type of system London would need, including in Singapore, which has the world’s most advanced arrangements.

None of this will deter the Hall campaign, which, as ULEZ rage fades, will need a new scare story to tell of a “war on motorists” being waged by Khan, no matter how much he denies it. After all, at the last election Tory candidate Shaun Bailey flammed up the fiction of an imminent “outer London tax” to be levied on anyone crossing the Greater London border by car should Khan remain Mayor.

Needless, to say, no such “tax” has come anywhere near being levied. But the point, pre-election, was to spread misinformation, create anxiety and fuel voter rage. Get ready for more of all that, starting now.

Twitter: Dave Hill and On London. If you value On London and its writers, become a supporter or a paid subscriber to Dave’s Substack. Image from 2018 Mayor’s Transport Strategy.

You forget the impact of ULEZ on white van man and his allies the London taxi drivers – almost every one of whom is an anti Khan publicist. Now add the impact of LTNs on the earnings of uber and other minicab cab/delivery drivers and you have the reason why the Labour Party is distancing itself from both outer London ULEZ

and LTN extensions.

Hi Philip. There is a mention of vans in the article. The compliance rate is much lower but so is the number of vans, so, statistically speaking, a relatively small part of the overall picture.