The results of last week’s European Parliament election were dramatic. The Liberal Democrats “won” London, Labour came second and the newly organised Brexit Party came in third. In terms of MEPs, the Lib Dems won three (gaining three), Labour won two (losing two), Brexit Party won two (gaining one from UKIP’s showing in 2014) and the Greens won one (no change). London was an island within England, being the only region which did not give a plurality to Nigel Farage’s new vehicle. Despite these being stand-alone European elections, while the previous election in 2014 ran alongside borough elections, turnout was up from 37.4 per cent to 41.3 per cent in London, reflecting heightened political tensions.

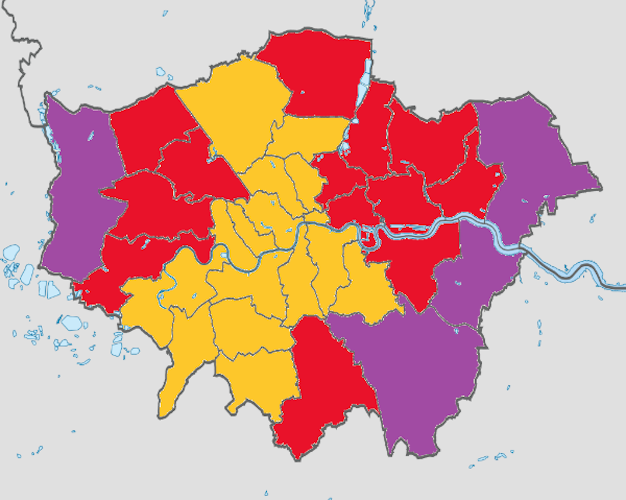

We have had a little time to digest the results, and reflect on what they mean for the future. Which of London’s boroughs supported which party, and as far as we can tell which of the foundations of the old two party politics is still left standing? What can we say about London’s attitude to Brexit and how it has changed since 2016? The map below shows the leading party in each borough.

Key: Red, Labour; Gold, Lib Dem; Purple, Brexit Party

The vote was highly fragmented: in some boroughs the “winning” party only polled a quarter of the vote. In a proportional election with many parties competing, we need to move away from the simplistic idea that winner takes all, and that all the other parties are somehow losers. The Greens, for instance, came third in their best boroughs, but the election can still be counted as a success for the party in that it increased its vote and retained its seat.It is still a very weird looking map that bears no relation to any previous political map of London. The fringes of the metropolis were nibbled by the populist-nationalist party that led in the rest of England, Labour led in the east and most of the middle London suburbs like Ealing, Enfield and Redbridge, and the Lib Dems were ahead in all but three Inner London boroughs plus suburbs to the south west and north. Let’s have a look round this unfamiliar version of political London.

Brexit Party vote share and borough ranking

Key: Purple, first; Pink, second; Grey-Blue, third; Grey, fourth.

The Brexit Party’s vote share of 18 per cent was high enough to win two London MEPs and the party came top in four boroughs. However, Farage’s party was very weak in inner London and achieved its worst result in Hackney (six per cent). Support for the continuing UKIP party was highest in the same areas as those where the Brexit Party did best.

Liberal Democrat vote share and borough ranking

The big winners of the London European Election were the Liberal Democrats, who topped the poll in the capital for the first time in well over a century and gained three MEPs.

The Lib Dem vote was strongest in Richmond and Kingston, where the party has long been successful, and they also achieved some very solid results in Inner London boroughs like Camden and Lewisham, where they had previously enjoyed success at local level until that was stopped dead by their national coalition with the Conservatives in 2010.

It was particularly pleasing for them to beat Labour in some Corbynite fiefdoms such as Islington and Haringey. But the novel element in their electoral coalition was a huge vote that appeared from nowhere and made them the biggest party in boroughs such as Wandsworth, Hammersmith & Fulham and Westminster, which have been dominated by the two big parties for decades.

Labour vote share and borough ranking

Key: Red, first; Orange, second; Yellow, third; Grey, fourth or worse.

What saved Labour from worse was the loyalty of its support among BAME Londoners. This saved Labour’s blushes a little in the working class East (Newham, Barking & Dagenham) and the suburban West (Ealing, Hounslow) and kept its support higher than in 2009 when it had lost Muslim votes in particular to the Respect party. None of the rival parties did much to appeal to these voters, and Labour’s ambivalence about Brexit might still have some resonance with a group of voters who were unenthusiastic about either side in the 2016 referendum.

But this is the chilliest of cold comfort; 2009 should have been an absolute nadir as it came against the background of economic slump, the expenses scandal and a very unpopular Prime Minister. Labour is also in trouble with much of its core vote. It has been bleeding traditional support among the white working class in outer London for several elections and this continued. What is new is the collapse in support among young, educated voters, and liberal professionals – groups where Labour support has been rising. The coalition that won Labour such impressive levels of support in 2017 has been smashed, as the Lib Dems came out ahead in Islington, Lambeth and Lewisham.

The Conservatives

There is little point in producing a map of the Conservative vote. Their performance was uniformly grim. The Tories did not make even third place in a single London borough. Their highest share of the vote was 15 per cent, which they managed in Harrow. They were badly squeezed between the Brexit Party and the Lib Dems. They had already lost a lot of their white middle-class suburban support to UKIP by 2014, and in 2019 another part broke off and went over to Farage’s newer vehicle.

The movement in this direction was less dramatic in London, even in Brexity boroughs like Havering, than it was in much of the rest of the country. The dramatic development in 2019 was the disappearance of most of the Conservative vote in the more affluent boroughs – the homes of high-paid professionals and the very wealthy alike. Below 10 per cent in Wandsworth and a poor fourth in Kensington & Chelsea are results no healthy centre-right party would ever wish to contemplate.

True, it was a weird election and it does not mean that the Tories will poll anywhere near as badly in a mayoral or general election context. But once voters’ loyalty to a party is broken in an election, it never completely comes back. The European election result points to the horrible dilemma shaping up for Conservatives: winning back one of the two wings of its core vote will alienate the other. Is it possible any more for the same party to win both Bexley and Wandsworth in a national or London-wide election? Will it be any more likely to do so within a few months, after the Conservatives have gone full “no deal” or been forced into another referendum?

The Green Party and Change UK

The other two significant parties can be fairly quickly dealt with. The Greens did well, increasing their vote share since 2014 in every borough except Kingston and Richmond (where their 2014 total was swelled by disgruntled Lib Dems, who went back in 2019). Their vote was distributed similarly to how it has been in the past, with concentrations in the inner east and south (Hackney, Lewisham, Lambeth). Change UK had a very disappointing result – 5.2 per cent across London as a whole. Their best borough was Lambeth (8.1 per cent) where Chuka Umunna is an MP, and they also topped seven per cent in Barnet, the City and Wandsworth. This level of support would be enough to translate into a London Assembly seat in 2020, should it be sustained, but it is hardly breaking the mould and the future looks bleak without reaching an understanding with the Lib Dems.

Another referendum?

What about the implications for a theoretical future referendum – whether Londoners want one, and how they might vote in it if it happens? Trying to extrapolate a referendum result from the European Parliament elections is not a respectable activity. The choice is different, the turnout is lower and people – particularly those who stuck with Labour and Conservative – don’t necessarily vote on their Brexit preference. Lord Ashcroft’s polling estimated that the Conservative vote was 67 per cent Leave and Labour’s was 63 per cent Remain. The distribution of Tory Remainers and Labour Leavers will vary between boroughs, so mechanically attributing voters to one side or another is flawed.

However – like many psephologists, I suspect – I have done a few such projections based on different assumptions. They are not robust enough to be published, but there does seem to have been a swing towards Remain, perhaps particularly in boroughs that were only narrowly Remain in 2016 (Ealing, Hounslow, Enfield). Sutton and Hillingdon might have switched from Leave to Remain, leaving three boroughs in the Leave column (Barking & Dagenham, Bexley, Havering). But it might just be a result of differential turnout, particularly for the Lib Dems given their strong local machine in Sutton.

The model results, despite being shaky, have an interesting implication. If Ashcroft’s numbers apply, one third of London’s Leave supporters, compared to a quarter nationwide, voted for Labour or the Tories. This may suggest that London’s Brexiters (except the ones in Bexley, Havering and Sutton) are more moderate than those in the rest of the country. If they are typical, and the vote share for UKIP and the Brexit Party combined accounts for three-quarters of them, then Remain is massively ahead in London. All one can say is that there is no sign that Londoners are becoming reconciled to Brexit and some indication that the opposite is true.

OnLondon.co.uk is dedicated to providing fair and thorough coverage of London’s politics, development and culture. The site depends on donations from readers and is also seeking support from suitable organisations in order to get bigger and better. Read more about that here. Thank you.