As a capital city, London has an important job to do. It gives a home to national government. It is a base for business and a hub for jobs and opportunity. It showcases the country on an international stage. It supports the nation.

But is London doing its job properly? People across the country feel locked out of the city, seeing it as expensive, inaccessible and unfriendly. Brexit underlined the fact that London isn’t working for everyone; a recent poll commissioned by Centre for London found that Leave voters across Great Britain feel more alienated from the capital overall than Remain voters. The vote to leave the EU has often been interpreted as a rejection of the status quo and a desire for change. But before London can change for the better, first we need to understand how the city is perceived by Leave voters.

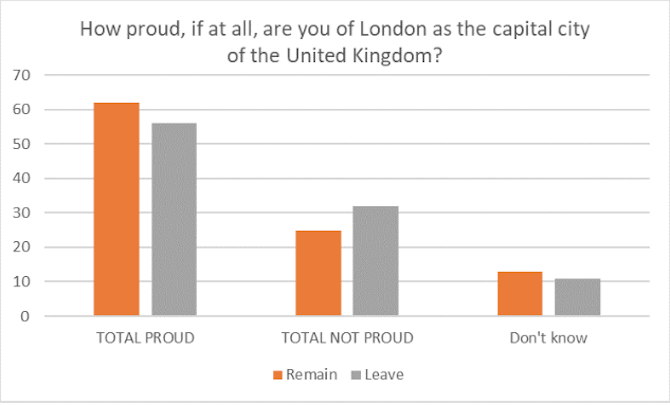

Leave voters were less likely to express pride in London as the capital city of the UK than Remain voters. But a majority of both groups still said that they were proud of London as a capital (including 51 per cent in the North of England, and an average of 59 per cent across England only). So whilst there are differences in opinion along Brexit lines, these are far from terminal.

The two most popular words chosen to describe Londoners themselves also split on a Remain-Leave basis, with Remainers more likely to describe Londoners as “diverse” than Leavers were, and Leavers more likely than Remainers to think the capital’s residents “arrogant”.

Perhaps most surprisingly, despite their distaste for London as a place, Leave voters outside London are notably more likely than Remain voters to want to keep things where they are in the UK.

Both Remain and Leave voters were particularly disinterested in “decentralising” the country to make it “fairer”, by moving institutions such as parliament, government departments, the national news media or national museums and galleries out of London. But Leave voters were even less interested.

So what does it all mean? Overall, it does appear that Leave voters hold more negative views of the capital than Remain voters. They are less likely to express pride in London, more likely to pick negative words to describe it, and more likely to view its occupants as “arrogant”. These differences are small, but are consistent enough to suggest a pattern. The size of these differences also suggests that this is not unsolvable; although Leave voters are also less inclined to take radical action to address London’s dominance by moving institutions out of the capital.

The radical devolution of power to a more local level across the country (which would not require physically moving institutions out of London) could be one way of reconnecting voters with the decisions that affect their lives. And it could enable better decision-making across the country too, helping to boost growth in regions outside of the capital. As the most prominent devolved region in contemporary Britain, London can play a powerful role in demonstrating the benefits of devolution, as well as working to actively support its regional peers, both publicly and behind the scenes.

But this alone is not enough. The process of negotiating Brexit has, ironically, left little space for serious thinking about how to address the issue. On top of this, the government’s own forecasts predict that Brexit will have a much stronger negative economic impact on regions outside of the capital, regardless of the outcome of the ongoing negotiations. All post-Brexit scenarios are therefore expected to see regional inequalities worsen. New thinking on how to mitigate these effects is therefore extremely important. The capital must look to play a role in bringing people back together, and reconnect voters with the decisions that affect their lives – and Centre for London’s London and the UK project is seeking to do just that.

Jack Brown, a frequent On London contributor, is senior researcher at Centre for London, which originally published this article. All the figures it contains, unless otherwise stated, are from pollsters YouGov.

I think decentralisation purely for political reasons (to attempt to alter inequality) won’t work. All research on the economy of cities points to urban centres as being central to economic growth, and that regions benefit by being in proximity to a thriving city.

As someone who lives in East Anglia and has studied economic marginalisation there, I’d say the situation is compounded by poor IT infrastructure, poor transport links and poor governance. If the first two things were resolved East Anglia could make more of its proximity to London, and if the third changed there might be more proactivity to reform the economy, society and culture of the region.