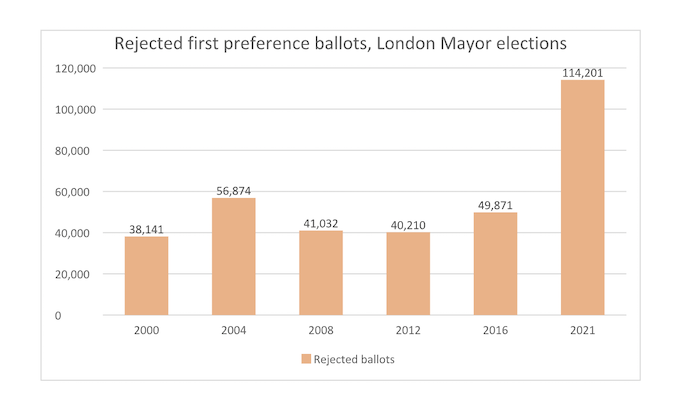

The London Mayor election of May 2021 has set an unwelcome record – it had the highest proportion of spoiled ballots of any major British election in recent history. Among Londoners who took the trouble to return a ballot paper, 4.3 per cent of them – 114,201 people – had their ballots thrown out.

There are always a few people who spoil their ballot in any election, because they dislike all the options or because they don’t understand what they are supposed to do with the ballot paper and leave it blank, sign it, or mark it in a way that doesn’t clearly convey what they intend. The rate of rejected ballots in London mayoral elections has tended to jog along at around two per cent, but in 2021 it more than doubled.

The increase in rejected first preference ballots was concentrated in the “voting for too many candidates” category, which rocketed from 32,217 such votes in 2016 to 87,214 of them in 2021. The number of unmarked and uncertain ballots also rose, but by nowhere near as much. This sort of ballot problem is very rarely intentional (unlike blank ballots or those where someone has scrawled “stuff the lot of you” across the paper). It is usually because the voter has attempted to express their political choices but been confused about how to do it.

Among the London Assembly constituencies, the rate of rejection was highest in City & East (6.7 per cent) and lowest in Bexley & Bromley (2.8 per cent). We shall await further detail, but this suggests that the rejected ballots came disproportionally from deprived areas and those with large minority populations. Had these votes been able to be counted, it seems likely that Sadiq Khan’s first-round lead would have been a bit larger.

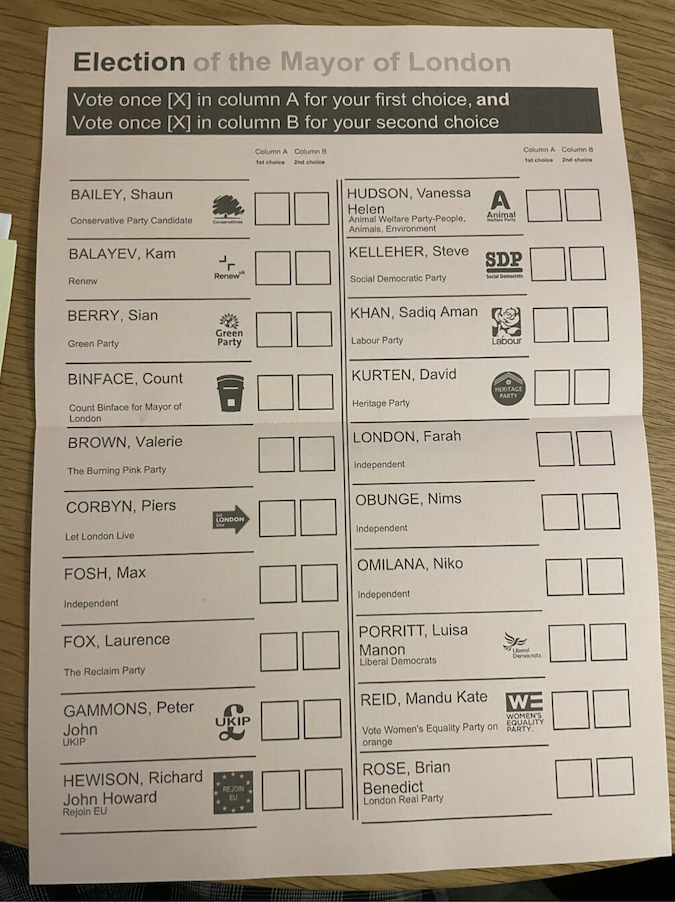

When there is a jump in the number of rejected ballots, it is usually the format of the ballot paper or the instructions on it that are to blame. The 2021 mayoral ballot paper is certainly among the more confusing that has been deployed in a British election (see example below).

(Image via countbinface.com)

The problem here is the combination of the instruction and the idea of “two columns”. You are told in big letters at the top to vote in column A and then column B, but the definition of what this means is given in the small print. There are two columns of boxes stretched across a single list of candidates spread over two columns!

It would not be unreasonable for a voter to examine this ballot paper and see two prominent columns – one from Bailey down to Hewison, the other from Hudson to Rose – and assume these are the principal columns and then conclude that they can vote for one from the first and one from the second.

Given that over half the votes cast in the first column (other than for Bailey) were for Sian Berry, whose supporters directed their second preferences strongly towards Khan, it is plausible that the principal victims of this problem were people who intended to vote Green 1, Labour 2 for Mayor.

Britain’s most infamous spoiled ballot paper fiasco was in the Scottish Parliament elections in 2007, when a ballot redesign sowed a certain amount of confusion among voters. The 2007 spoiled ballots stushie in Scotland arose from a rejection rate of 2.9 per cent for the regional list vote and 4.1 per cent for the constituency vote. Even at its worst, this was still less than we had in London last week.

The days after the Scottish vote were dominated by media coverage of the problem, and the Electoral Commission convened an external inquiry into what had happened. The outcome, the Gould Report was published in October 2007 and made severely critical remarks about the approach to the election: “Almost without exception, the voter was treated as an afterthought.”

Gould recommended that governments should not make changes to election rules within six months of a poll and noted that the ballot paper redesign had been done on the basis of very little research into how voters would respond.

In the 2021 London case, it is fair to concede that London Elects, which organises the elections, was in a difficult position. The election had been postponed once and there was an element of uncertainty until nearly the beginning of the formal campaign as to whether it would have to be postponed again.

The design problem was caused largely by the unprecedentedly large number of candidates contesting the election – the template had been able to cope with 12 candidates in 2016 but 20 was too many for one column without using either a very long ballot paper or print that was too small for people with impaired vision. Electronic counting of the ballot papers – excellent and reliable in principle – also imposes constraints on ballot design and size. But the wording and design of the paper used in 2021 surely contributed to the poor outcome too.

As with Scotland in 2007, London’s spoiled ballots last week deserve a dispassionate inquiry. What were the decisions that led to this duff ballot paper? Could the disenfranchisement have been avoided? What were the thought processes that led people to record so many invalid votes? Would it be simpler just to ask voters to vote, in a single column of boxes, “1” for their first choice and “2” for their second choice rather than placing “x” in two different places?

The Gould inquiry was permitted to look at what people had put on the rejected ballots and a London inquiry should do the same. Perhaps the answer is to make it less easy for vanity candidates to stand. Requiring a lot more signatures for a valid nomination than usual seems attractive – the threshold was lowered for this year because of Covid – and a higher deposit might be useful too.

The government has already proposed abolishing the right to express a second preference, contrary to what Londoners voted for in the 1998 referendum that resulted in the mayoralty’s creation. Easing the confusion might be a by-product of this nakedly self-interested policy, but it will create a larger problem for the 25 per cent of voters who want to have their true first preferences counted rather than be corralled into dreary tactical voting for the main candidates.

Preference voting widens choice and enables people to express their political views more meaningfully and accurately. One badly designed ballot paper is no reason to ditch it.

OnLondon.co.uk provides in-depth coverage of the UK capital’s politics, development and culture. It depends greatly on donations from readers. Give £5 a month or £50 a year and you will receive the On London Extra Thursday email, which rounds up London news, views and information from a wide range of sources, plus special offers and free entry to events. Click here to donate directly or contact davehillonlondon@gmail.com for bank account details.

I entirely agree with your description of how confusing the mayoral ballot paper was.

Although the instructions had a large ‘A’ and ‘B’, the 4 columns only had tiny A’s and B’s. And it would have helped if the instructions had said e.g. “Vote once [X] in a column A” rather than just “… in column A”. A firmer separation between the two halves could have helped, with “Candidates and voting columns continued on right-hand half of the paper” at the bottom of the left-hand half.

Also, the instructions are misleading anyway – I’m quite sure not expressing any second preference does not invalidate your first choice, yet the instructions imply you must enter a choice in column B.

But I think that your suggestions for how to constrain the number of candidates are unnecessarily punitive – it already normally needs 330 signatures, a steep time-consuming requirement for a small organisation; and £20,000 is a huge sum to raise for most people (half of that is for inclusion in the booklet, and you can hardly be a serious candidate without being in it).

Besides, there are more imaginative ways of tweaking it:

> The deposit/booklet split could be shifted – say £18,000 to stand, and £2000 for the booklet (4 of the 20 were not included in that, this time)

> For such a large amount, there shouldn’t be just a single threshold (5%) for the deposit’s return. You could get a little bit back if you get say 1%, rising to quite a bit back for 5%, most back for 10%, but not all of it unless you get 15%. This should focus attention of the minor but serious (in their own minds at any rate!) parties standing on a similar platform, to seek out each other and combine their efforts instead of competing, in the hope of maximizing the proportion refunded. For example, at least 4 of the 20 candidates were standing on a UKIP/pro-motorist/anti-lockdown/anti-censorship type of right-wing platform, and, depending on which ones you count, had a combined vote total around the 4% level. The total outlay could then even be increased, as ‘serious’ parties like the LibDems and a combined UKIP legacy type party could be confident of getting some of it back.

One test for any changes to nomination requirements will invariably be the ability of significant parties’ branches in weaker areas to meet them. Although this proposal is focused on the mayoralty with such a high amount it would be hard to keep the principles out of other elections and this would cause real concern in areas where significant parties struggle to get 15% and likely do not have a local branch overflowing with spare cash. And similarly they will be deeply concerned about higher nomination requirements.

Having collected signatures in boroughs for mayoral candidates both this year and in more normal times I think ten signatures per borough is usually a reasonable threshold. It requires going to multiple households and having some level of effort, whether that’s organisation on the ground or just having a campaign supporter knocking on endless doors. Two signatures per borough was understandable because of the lockdown but very easy to get from a single location – it was interesting to see multiple candidates appealing on Twitter for signatures in certain boroughs (Rejoin EU hunting signatures in Barking & Dagenham stood out) and they would have found this a much harder task if they’d had to get ten signatures when the volunteers may well have been scattered all over a borough.