Nowadays, it can feel as if you are never more than ten minutes away from someone declaring that “London is not an English city any more”. Sometimes, the trope is rolled out by right-wing social media personalities like Laurence Fox, most recently in the wake of the Peckham Hair and Cosmetics incident. Sometimes it pops up in below-the-line comments on London news stories, usually posted by someone like “BromleyBoy365” from his base in Benalmadena.

Earlier this month, former UKIP mayoral candidate and London Assembly member Peter Whittle (picture below) dedicated a 35-minute video to the theme under the aegis of the New Culture Forum, a Tufton Street think tank focused on “challenging the orthodoxies dominant in our institutions, public life and wider culture”. I watched it so you don’t have to (though something like 388,000 other people have so far).

Whittle’s opening statement, delivered while wearing a brass-buttoned waistcoat that makes you wonder if he is going to burst into a Michael Bublé medley for the early-bird diners, sets out his stall:

“London has changed. Not just in the organic way that history usually demands but drastically, irrevocably and in the space of a generation. It is not really a British city, much less an English one. Unprecedented demographic change has seen to that. And its character, its very essence, once based on centuries of shared history and experience, is now defined by what are called its “values”, a set of modern beliefs to which the modern Londoner should sign up.”

There are four elements to his argument: that London has experienced unprecedented demographic change in recent decades; that this has stopped the city being British; that it has also diluted London’s character and shared history; and that Londoners are now being required to sign up to an alternative set of values. At least three of them are nonsense.

To begin on Whittle’s strongest ground, London has undoubtedly seen dramatic population growth in recent decades, partly driven by international migration at a time when migration has risen across the world. Since 2001, the proportion of Londoners born in the UK has fallen from 73 to 59 per cent.

By way of comparison, if you go back to 1901, a previous high point of global connectivity, London had 135,000 “foreign-born” citizens. These represented just three per cent of its population, yet that was almost ten times the proportion living in the rest of England and Wales. If you add people born in Ireland and the colonies of the British Empire, the proportion of people we would now regard as “foreign-born” rises to about five per cent.

So, while London’s international population was far smaller at the start of the 20th Century than it is today, it was also much larger than everywhere else in the UK and had been growing fast in previous decades. The London of that time did not experience international immigration to the same extent as the city has in recent years, but it has always had the global character of a port city. And it has always had people who disliked that character. The 12th Century chronicler (and antisemite) Richard of Devizes wrote disdainfully of the capital: “All sorts of men crowd together there from every country under the heavens. Each race brings its own vices and its own customs to the city.”

Has more recent immigration stopped London being British? From the first few minutes of the film, Whittle and his interviewees, Rafe Heydel-Mankoo, a New Culture Forum “senior fellow” whose website describes him as “one of North America’s leading royal commentators”, and Alp Mehmet, chairman of Migration Watch UK and a former UK Ambassador to Iceland, chuck around terms like “British”, “foreign-born” and “white British”, as if they are interchangeable.

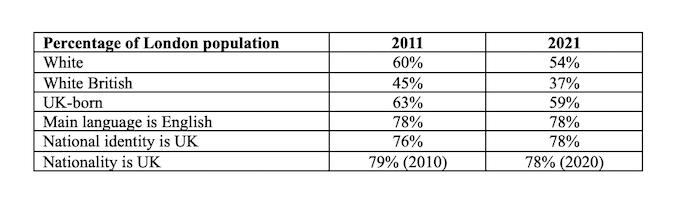

They clearly are not, as even a brief look at recent population data show. The figures below are from the 2021 Census (helpfully presented in one place here) and the Office for National Statistics Annual Population Survey for nationality.

The terms used in this context matter. So when Peter Whittle speaks of a decline in the ‘indigenous’ population when referring to ‘White British’ people, or talks of “the people who celebrate the lack of British or English people in London” when around four out of five Londoners are UK nationals, he is eliding concepts in a pretty inflammatory manner.

Mehmet worries that, unlike previous immigrants, these new arrivals don’t speak English. But, in fact, only around four per cent of Londoners don’t speak English well, according to the Census. He also says they don’t assimilate, contrasting them, hilariously, with British expats who apparently “do learn the language, by and large, and mix with the locals”. Whittle picks up this theme, saying “to have a strong identity, a city has to continue to pass on not just its particular traditions and shared history, but also the culture, language and multitude of nuances that make it unique”.

The 1901 Census report shows how mythic this Golden Age of a perfectly homogeneous London is. In some parts of the city, the impact of immigration was acute and disruptive at that time. For example, in Stepney the foreign-born population rose from six to 18 per cent between 1881 and 1901. The Census report notes the conclusion of a Royal Commission on Alien Immigration, “that the greatest evils produced by the presence of the Alien Immigrants here are the overcrowding caused by them in certain districts of London, and the consequent displacement of the native Population”.

Challenges with assimilation can also be seen in the extraordinary efforts made in 1901 to enable recently-arrived Jewish refugees, whose persecution in Tsarist Russia made them understandably suspicious of officialdom, to participate in the Census: there were leaflets in Yiddish and German, outreach workers to help fill in the forms and statements read out in synagogues.

Furthermore, international migration was only one part of the story. Migration from within the UK was a powerful force in London’s growth in the 19th Century. In 1901, one third of Londoners had been born outside the city. In 1851, the proportion had been an even higher 40 per cent. A Victorian dock-worker might have found he had no more in common with a Sussex peasant than with a Russian tailor in terms of shared history and experience.

It is also very unclear what the common culture Whittle cites and claims is so threatened by immigration might have actually been. The film intersperses talking heads with archive footage of royal occasions, Winston Churchill and old buses swinging around Piccadilly Circus. But while Mehmet pours scorn on glib markers of Britishness such as “fish and chips, warm beer, cricket, adhering to justice”, Whittle’s film never quite says what it believes London’s lost “communal customs, practices and culture” are.

What they most certainly are not, Mehmet argues, are “the values that Sadiq Khan tells us we must sign up to in order to be a Londoner”. But I don’t think the Mayor has ever said anything of the sort. Khan has talked of London’s values, but in descriptive rather than prescriptive terms. Whittle is particularly exercised by the Mayor’s often-repeated statements about London’s diversity, such as:

“For generations, London has served as a shining example of how people from different countries, cultures and classes can live side-by-side and prosper together. That’s because, by and large, Londoners don’t just tolerate each other’s differences, they respect, embrace and celebrate them – recognising that our diversity is not simply an added extra but one of our most valuable assets.”

I happen to think this slightly hyperbolic, though harmlessly so: yes, thronged streets for Pride and Carnival show that many Londoners do actively celebrate diversity, but many others just happily rub along with a variety of their fellow citizens. But more importantly, Khan is not saying what the city should be but what it is. Representing the capital in this way, to itself as well as to national government and the world, seems central to the Mayor of London’s role. The theme of diversity has been emphasised by all three London Mayors to date.

For Whittle and his interviewees, however, diversity is not something to be celebrated. “Diversity is weakness,” Mehmet asserts, “if you are talking about communities holding together.” But no evidence for this is cited. And a cursory look at studies of the issue reveals mixed findings, with some arguing that diversity actually increases social cohesion as long as segregation between different groups doesn’t reverse this beneficial effect.

The film moves on from diversity to attack a predictable litany of liberal articles of faith: belief in the climate crisis and support for “the war on motorists”, Black Lives Matter and “decolonisation” of statues, on which subject Whittle shows footage of himself as an Assembly member berating a bored-looking Sadiq Khan. It is the “white middle-class liberals” – the wrong sort of “White British” – who sign up to these, Whittle says, and who will ensure Khan is re-elected.

By the end, it all feels a bit sad and sour. These people don’t really like London or Londoners. They give the impression that they haven’t been in the city recently. Heydel-Mankoo says you never see people chatting in its streets or shops any longer and that Londoners’ trust in other people they encounter has declined. In fact, such levels of trust are around the UK average in London and higher than in most other countries.

Of course, London has its tensions and injustices, as all big cities do. But the city of suspicion and segregation Whittle’s film portrays seems a world away from my own experience and that of others. Look at the thousands of people mixing on football terraces, in pubs and nightclubs every weekend; the lively conversations of elderly Irish and Jamaican shoppers in Brixton market; the brief moments of connection on late-night tubes and buses.

Whittle ends by referring to a Roman Polanski quote: “Los Angeles is the most beautiful city in the world, as long as seen at night and from a distance.” As with LA and Polanski, I suspect London will be happy for Whittle to keep his distance.

X/Twitter: Richard Brown and On London. If you value On London and its writers, become a supporter or a paid subscriber to publisher and editor Dave Hill’s Substack for just £5 a month or £50 a year.