Making the case for London has been complicated during the pandemic. It risks conflict with the “metropolitan elite” myths so fondly fostered by government (and so ably skewered by my former colleague Jack Brown on Monday’s Start the Week). Like many civic leaders, Sadiq Khan has been trying to tell a story of devastating impact to a seemingly indifferent government, while also trying to entice workers and tourists back into a renascent capital by reminding them of all London has to offer.

The pandemic has indeed had a particularly brutal impact on London’s citizens and economy, but recent figures suggest the tide may be beginning to turn. Tube and bus ridership is higher than any time since March 2020, though still up to 50 per cent below pre-pandemic levels. Google mobility data also shows a slight return to Central London, though more for retail and recreation than for work (which accords with higher public transport use at weekends).

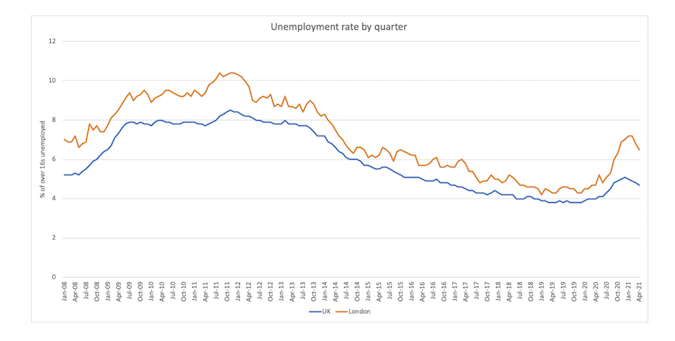

And, according to the latest ONS figures, London’s unemployment rate has also dropped, falling from 7.5 per cent in the three months to January, to 6.5 per cent in the three months to April. Unemployment is still higher than any other region’s, London boroughs still have some of the highest claimant counts and furlough rates in the country, and the economic impact of coronavirus has hit specific demographic groups hardest – but there are glimmers of hope.

It’s worth looking back to the last recession and recovery when London has hit hardest but recovered fastest. Could history repeat itself? As the chart below shows, London’s unemployment rate rose sharply ten years ago, and was more than two points higher than the UK’s in mid-2011, but then fell much more quickly, roughly tracking the national rate from 2014. A similar gap opened up last year, but has begun to narrow since January.

Unfortunately for today’s London there were specific features of the 2011/12 recovery that favoured the capital. Quantitative easing, the government’s response to the financial crisis, diverted investment into booming equity and housing markets. And the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, though they may have had a minimal direct impact on spending – most of the construction was complete by 2012 and Olympic Games years displace normal tourism expenditure – were a powerful showcase for the UK internationally, and for London in particular.

Added to this, ten years ago, Boris Johnson when Mayor of London was keen to make the case for the capital. He was able to persuade the coalition government that starving London of cash was no way to help the rest of the country, so projects such as Crossrail and Olympic Park legacy development went ahead.

None of these factors are present today. Rather than being boosted by cheap money, financial services have been sidelined in Brexit negotiations in favour of more picturesque and politically salient (but far less productive) industries like fisheries. Big infrastructure projects, such as the redevelopment of Euston Station for HS2, are being squeezed, hopes of a swift return to international travel are receding, and the narrative of “levelling up” looks pretty hostile to London and its nine million citizens.

At the G7 Summit last weekend, Prime Minister Johnson warned against repeating the mistakes of the ten years ago, when (as he didn’t quite say) austerity extended and deepened the impact of the recession for many citizens and communities. This is right, but the correct lesson is to extend support wherever it is needed to “level up” the prosperity and life chances of citizens and communities, not to stall the UK’s economic engine in pursuit of headlines or electoral advantage.

Richard Brown is a freelance writer and consultant who has worked for an array of major London organisations, including Centre for London, the Greater London Authority and the London Development Agency. This article also appears on Richard’s website. Follow Richard on Twitter.

Photograph: Liverpool Street station entrance.

On London is a small but influential website which strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. It depends on financial help from readers and is able to offer them something in return. Please consider becoming a supporter. Details here.

If London was having such a good time post 2008 how come more British people in that period chose to leave London than come to it? If it wasn’t for weak European economies then London’s population probably would have already been stagnating, since migrants came to London to find work. What sort of economic growth produces a net loss in the domestic population? London needs to become a liveable city. Only the asset rich benefited from the last decade of growth in the Capital. If you were renting, apart from getting some experience on your CV, London has not been particularly good for you. The new mantra for London should be less ‘London is Open’ and more ‘London is Liveable’. If you don’t fix the cost of living crisis people will simply keep leaving no matter how many jobs are in the Capital.