It could be argued that Bishopsgate should be renamed Shakespeare Street because of William Shakespeare’s associations with it. The great writer would have walked along it regularly, as it was the main road north of the Thames on the journey between the south bank of the river, where the Globe and the Rose theatres were, and Shoreditch, where the Curtain and the Theatre playhouses were.

We also know that Shakespeare lived for a while in the parish of St Helens church, close to where the Gherkin now stands. As a previous piece in this series has documented, his plays were staged at City inns such as the Crosskeys in Gracechurch Street. And several scenes from Richard III were set at the nearby Crosby Place mansion whose location now forms part of the footprint of Tower 42.

It is less well known that Bishopsgate also has links with people claimed by some to have been the true writers of works attributed to Shakespeare. Competing accounts of the source of Shakespeare’s canon form the longest who-done-it in literary history, one that refuses to go away despite being virtually ignored by those – known as Stratfordians – who firmly believe that the output attributed to Shakespeare was indeed created by the glovemaker’s son from Stratford.

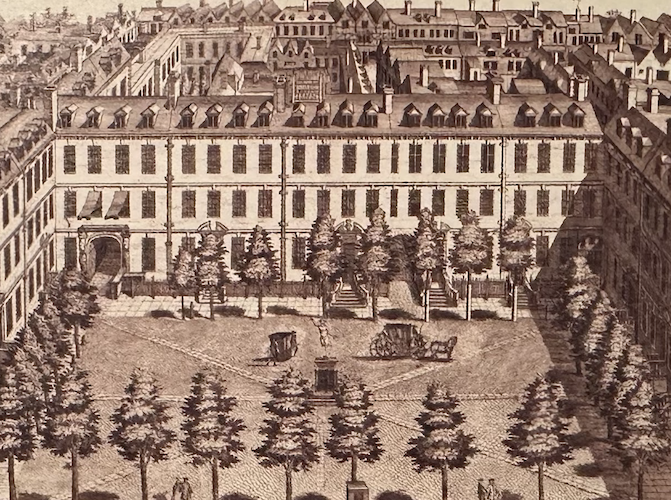

For a long time, beginning with the work of John Thomas Looney in 1920, the foremost candidate among the dozens of alternatives proposed has been Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford. And guess what? It was this same Earl of Oxford who, in 1580, purchased a palatial home (main picture) in Bishopsgate opposite St Botolph’s-without-Bishopsgate church. It was a magnificent dwelling, built by a man called Jasper Fisher in the late 16th Century. Fisher must have been reasonably well off, as he was a member of the Goldsmiths’ livery company, but constructing a mansion on this scale was beyond his means.

John Stow, the 16th century historian, called it “a large and beautifull house with Gardens of pleasure, bowling Alleys and sumptuously builded”. He reported that Fisher spent all his funds building it and owed money to many people, leading locals to refer to the result as “Fisher’s Folly”. Fisher died in 1579, heavily in debt.

The Earl of Oxford’s tenure lasted from 1580 until 1588, so it would have coincided with the period when Shakespeare was thinking about his early plays, such as The Two Gentlemen of Verona and The Taming of the Shrew, both of which were written or first performed at the turn of the decade.

Oxford was certainly a deeply literary person. Charles Wisner Barrell, an American art critic and a supporter of the view that Oxford was the “real” Shakespeare, suggested in 1945 that Oxford acquired his impressive home “as headquarters for the school of poets and dramatists who openly acknowledged his patronage and leadership.”

Fisher’s Folly was sold by Oxford to Sir William Cornwallis, and Stow’s The Survey of London, in a section published in 1603, says of the property, “It now belongeth to Sir Roger Manars”, by whom he is assumed to have meant Roger Manners, the 5th Earl of Rutland.

This is curious because in 1907 German author Burkhard Herrmann argued that Rutland was the real author of Shakespeare’s works. Rutland was ranked seventh in a top-ten list of “the most notable possible authors of the works of Shakespeare” as determined by TopTenz.net in September 2011.

That makes two would-be Shakespeares living in the same mansion, albeit separated by a few years. It gets curiouser when we learn that Rutland was friends with Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, who was Shakespeare’s patron. When Rutland undertook the Grand Tour of Europe he studied at the University of Padua where The Taming of the Shrew was set and where two of his fellow students were apparently called Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, as if they had stepped out of Hamlet.

It gets curiouser still. St Botolph’s – shown in blue in the map above – is where the poet and writer Amelia Lanier was baptised and married. She is thought by some scholars to have been the “dark lady” of Shakespeare’s sonnets and by others to have been the actual Shakespeare. That makes three people alleged to have been the real authors of works accredited to Shakespeare living within a few hundred yards of each other – four if you include Shakespeare himself.

Lanier came from an Italian-Jewish background, and a recent book contending that she was really Shakespeare describes a litany of Jewish imagery in Shakespeare’s work, which I found impressive. I would have been more impressed had I not read another book a few months earlier arguing that Shakespeare must have been a Catholic because of all the Catholic imagery he deployed.

From 1620 until 1670 Fisher’s Folly, as it continued to be known, was taken over by the Earls of Devonshire to add to their collection of palatial residences and was renamed Devonshire House.

In 1678 that fascinating and controversial speculator Nicholas Barbon purchased what was by then called Old Devonshire House and proceeded to pull it down to make way for the profitable construction of small houses instead.

Barbon had a track record of demolishing aristocratic residences, such as Essex House and others in the Strand. He also designed Devonshire Square in the space where the Fisher mansion had stood before selling it, largely undeveloped, in 1682. But Devonshire Square is still there and well worth a visit. Today, it leads to an impressive glass-roofed entertainment and eating centre.

The best way to get there is to take a right turn off Bishopsgate along Houndsditch and then a left up a tiny street called, unsurprisingly, Barbon Alley, which leads you into what little remains of the site’s 450 years of history.

This is the tenth article in a series of 20 by Vic Keegan about locations of historical interest in the Eastern City part of the City of London, kindly supported by EC BID, which serves that area. The previous nine articles are here. On London’s policy on “supported content” can be read here.