The Kimpton Fitzroy Hotel stands imperiously in Russell Square displaying its thé-au-lait (“tea with milk”) terracotta frontage, including statues of four queens – Elizabeth I, Mary II, Victoria and Anne.

From 1900, when it was opened, until 2018, when it was relaunched under new owners, it was known by its original name of Hotel Russell, where early meetings of the Russell Group of universities took place. But the Fitzroy part of its present name is a nod to its architect, Charles Fitzroy Doll, from whom the term “dolled up” is derived due to his liking for decorative facades – in this case using material from the Doulton potteries in Lambeth.

Behind that facade lies a sumptuous interior with a story of its own. A feature of the Kimpton is its dining hall, which looks copied from that of the Titanic. Actually, it is the other way around – the dining room of the Titanic was copied from the hotel’s by its designer, Fitzroy himself. The hotel also contains a small bronze dragon called Lucky George, which is identical to one lost on the Titanic. A further connection is that some Titanic passengers spent the night at the hotel before boarding.

The site of the hotel has a previous, now buried, history thanks to Frederick Calvert, who, upon his father’s death in 1751, became the sixth Baron Baltimore (an Irish peerage) at the age of 20. As a result of this – would you believe it – he inherited Maryland in the United States, which had been in his family since Charles I gave it to his ancestor George Calvert, the 1st Baron Baltimore. The Mary in Maryland refers to Charles’s wife Henrietta Maria. It was a British colony the size of Belgium, which produced income from rents and taxes worth the equivalent of many millions today.

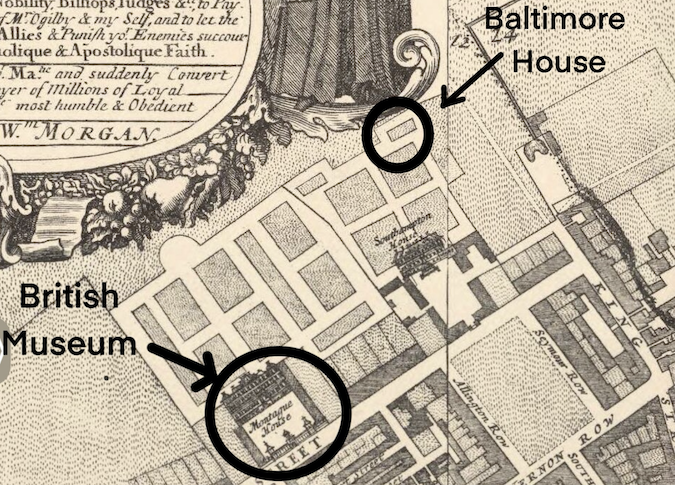

In 1759 the young Calvert used some of this income to build a mansion called Baltimore House in the gardens of the palatial Southampton House – later renamed Bedford House – in Great Russell Street, next door to Montagu House where the British Museum is today (see map below). Beyond lay open fields, marking the end of London. Baltimore House stood where the future Hotel Russell would later appear.

Frederick Calvert was an extraordinary man for whom sin might have been invented. An old Etonian, he presided over Maryland with almost feudal powers but never actually set foot there, preferring instead to squander his riches, which were mainly derived from tobacco and the slave trade. Unlike some contemporaries, who salved their consciences with good works, he blew it on often public debauchery.

And how! Calvert led what has been described as “an extravagant and often scandalous lifestyle” culminating in 1768 with an accusation of abduction and rape by Sarah Woodcock, a local beauty who ran a milliner’s shop in Tower Hill. An all-male jury acquitted him, but not many believed the verdict.

He fled the country soon after and travelled around Italy and then Constantinople, which he had to leave after being accused of keeping a private harem. It wasn’t so very private, as he was known to parade his entourage of five white women and one black one brazenly in public.

Calvert was so fascinated with the Ottoman Turks that on his return to England he pulled down part of Baltimore House in order to reconstruct it in the style of a Turkish harem. Following his death in Naples, Maryland was inherited by one of his numerous illegitimate children, Henry Harford, aged 13.

After that, Charles Powlett, the 3rd Duke of Bolton and a Whig politician, took a lease on Baltimore House and renamed it Bolton House. This restored its prestige, but only a little. Historian Edward Walford described Bolton as “equally eccentric” as Baltimore.

Powlett did some good deeds – in 1739 he was one of the founding governors of the nearby Foundling Hospital, which did sterling work for orphaned children. But he is mainly remembered for a long standing affair with the actress Lavinia Fenton, which started in 1728 and lasted until 1751, when his wife Lady Anne died. He then married Fenton, who by then had already borne him three children.

This relationship has been immortalised by William Hogarth, whose famous painting of John Gay’s Beggars Opera (above) shows the Duke, sitting on the right of the stage, eyeing Lavinia during a performance. Goodness.

This article is the 18th of 25 being written by Vic Keegan about locations of historical interest in Holborn, Farringdon, Clerkenwell, Bloomsbury and St Giles, kindly supported by the Central District Alliance business improvement district, which serves those areas. On London’s policy on “supported content” can be read here.