If you walk past 111 Cannon Street opposite the station you will see a protrusion at the foot of the Fidelity Investor Centre building. Don’t blink or you might miss what, since 2018, has been the latest special casing for an unprepossessing lump of oolitic limestone measuring 21 inches wide and 17 inches tall.

A Stonehenge stone it is not, but the object known as London Stone has been around for at least eleven centuries and long baffled experts. All have agreed it must mean something significant, and yet they don’t know quite what.

One of the earliest references to it can be detected in the name of Henry fitz Ailwin de Londonstane (“of London Stone”), the first Mayor of the City of London – from 1189 until his death in 1212 – who lived and had his business headquarters nearby.

Someone else who seemed to know its importance was Jack Cade, who, in 1450, is said to have struck it with his sword as his Kentish rebels stormed London in revolt against Henry VI. Cade is memorialised in William Shakespeare’s Henry VI – Part 2 in which he takes on the persona of John Mortimer, a claimant to the throne, and declares:

“Now is Mortimer lord of this city. And here, sitting

upon London Stone, I charge and command

that, of the city’s cost, the Pissing Conduit run

nothing but claret wine this first year of our reign.

And now henceforward it shall be treason for any

that calls me other than Lord Mortimer”

London Stone was originally positioned on the other side of the street, which was then called Candlewick Street after the trade that flourished there. But why was it there in the first place?

Antiquarian William Camden theorised in 1586 that it was a Roman milestone from which distances from London were measured. Historian John Stow in the 1598 Survey of London described what was then a much larger rock, “fixed in the ground verie deep, fastened with bars of iron”. Stow wrote that the stone was so hard it could break the wheels of passing carts. He added: “The cause why this stone was set there, the time when, or other memory is none”.

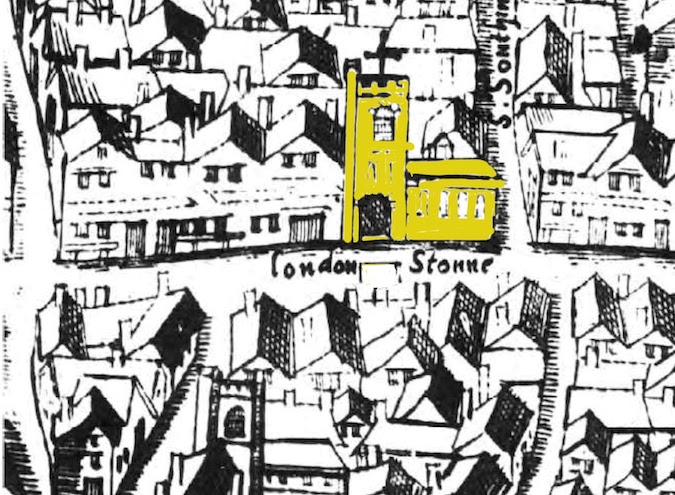

London Stone became damaged and diminished, perhaps including by the Great Fire of 1666. By 1742, in its much reduced form, it had been moved from the south side of the street to the north side and positioned next to the door of St Swithin’s Church, built by Christopher Wren after the Great Fire destroyed an earlier church there, itself built on the remains of others dating back to the 12th Century – an excellent example of the layers upon which London is built.

The stone was later moved to a part of the church’s south wall and then, in the 1820s, embedded and protected in a different part where it remained until 1962 when the Wren church, which had been badly damaged in World War II, was demolished.

By then the stone had been imbued with mystic significance, such as in William Blake’s 1831 poem They groan’d aloud on London Stone. At the start of this century, London biographer Peter Ackroyd wrote: “It was once London’s guardian spirit, and perhaps it still is.”

An office building replaced St Swithin’s, and London Stone was preserved in an alcove within it. Then, in 2016, planning permission was secured for a new office block to be constructed on the site, resulting in the stone being temporarily cared for and displayed by the Museum of London.

It was returned to Cannon Street in October 2018. Judging by the two images above it is now on more or less the same spot as when housed by St Swithin’s. The difference is that a House of Mammon has replaced a House of God.

If you visit London Stone be sure to also wander in the adjacent Salters’ Hall Court, where you will discover one of London’s smallest and most secluded gardens (see below). A space that used to be the St Swithin’s burial ground is now surrounded – I was going to say enshrouded – by enormous office blocks.

A curiosity is the statue (above, right) dedicated to Catrin Glyndwr, daughter of Owen Glyndwr, the Welsh nationalist who led a prolonged revolt against Henry IV. Catrin was buried in the church grounds in 1413 after being imprisoned in the Tower of London. She was married to Edmund Mortimer, who had a claim to the throne of England and was part of the same Mortimer dynasty with which Jack Cade would associate a few decades later. It is enough to give a psychogeographer collywobbles.

Top photo by GrindtXX, photo of the stone from Museum of London, all others by Vic Keegan.

This is the first article in a series of 20 by Vic Keegan about locations of historical interest in the Eastern City part of the City of London, kindly supported by the EC BID, which serves that area. On London’s policy on “supported content” can be read here.