The reigns of Elizabeth I and James I saw an explosion of literary talent in London that has never been matched. Plays by William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Middleton and others created during that period are still being staged around the world today.

They were mainly associated with playhouses such as the Globe, the Rose, the Swan and later the Blackfriars, all of them deliberately situated outside the confines of the City of London, whose puritanical rulers were opposed to plays, regarding them as lewd and degrading.

It is less well known that at about the same time, and in some cases slightly earlier, playhouses did nonetheless exist within the confines of the City. They were not purpose-built but instead attached to inns, either inside or outside, which is one of the reasons detailed records about them don’t exist.

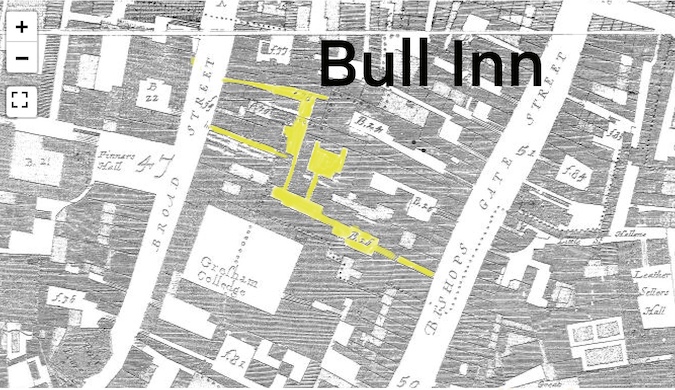

There were four of them in all. Two, the Cross Keys and the Bell, both indoor venues, were close to each other in Gracechurch Street, and a third, the Bull, was further up the road in Bishopsgate. The fourth, the Bel Savage (or La Belle Sauvage), was in Ludgate Hill.

If you walk north up Gracechurch Street today – or Gratious Street as it used to be called – from the Monument you will come to Bell Inn Yard, next to Wetherspoons. The original Bell Inn Yard, which existed from the 14th century, was destroyed in the Great Fire of London, but today’s entrance to it is almost certainly in the same place as the way in to the old Bell Inn and its theatre. Confusingly, the Bell Inn Yard sign has a plaque beneath it honouring the Cross Keys Inn, but it was actually located about 25 yards away.

These theatres came into their own after 1569 when the City authorities relaxed the rules allowing plays to be staged at inns in return for a payment of £40 – a hefty sum in those days. That situation lasted until 1594 when the Lord Mayor got the Privy Council to ban all use of City inns for theatre shows.

Shakespeare would have been familiar with Bishopsgate. If his footprints could be traced they would be everywhere. He would have often strolled or ridden from Shoreditch, where his plays were put on at The Theatre in Curtain Road, to London Bridge in order to cross the river to The Globe and the Rose. Also, we know for certain that he lived for a while in the neighbourhood of St Helen’s church, off Bishopsgate, because he is named in the tax records for the area for 1598. It is difficult to believe that he didn’t visit the inns of Bishopsgate too.

Were his plays performed at them? Julian Bowsher, an archaeologist who wrote Shakespeare’s London Theatreland, says that in 1594 the Lord Chamberlain said: “My new company of players have been accustomed for the better exercise of their qualities…to play this winter time within the city at the Crosskeys in Gracious Street”.

Actor troupe The Lord Chamberlain’s Men – later renamed The King’s Men after James ascended the throne – was Shakespeare’s company and had exclusive rights to perform his plays. Several scenes from one of his most famous works, Richard III, were set near Bishopsgate at Crosby Place. In one scene he tells the assassins he had hired to kill the Duke of Clarence: “When you have done, repair to Crosby Place.”

What was it like inside those theatres? They offered a mixture of serious entertainment and dating opportunities. A rare contemporary account by Stephen Gosson states: “In the playhouses at London, it is the fashion of youths to go first into the yard, and to carry their eye through every gallery, then like ravens, where they spy the carrion thither they fly, and press as near to the fairest as they can.”

It is not clear if Gosson was thinking of classic playhouses like the Globe or the inns of Bishopsgate and Gracechurch Street. Probably both. He gives the impression that at the Bull, where the stage was in the open air, the spectators were more restrained, perhaps because of its generous dimensions. Alleys leading to it stretched all the way from Bishopsgate to Broad Street.

The explosion of literary talent in early modern England could only have happened in London, which had entrepreneurs prepared to put their money behind the new theatres, aristocratic patronage – a sine qua non – royal approval, loose copyright laws and a rising population. It all happened in a small geographical area, which enabled clusters of playwrights to meet and collaborate. Bishopsgate and Gracechurch Street played a small but very important part.

This is the fifth article in a series of 20 by Vic Keegan about locations of historical interest in the Eastern City part of the City of London, kindly supported by the EC BID, which serves that area. On London’s policy on “supported content” can be read here.