If you take the Tube between Rotherhithe and Wapping stations you will be travelling through the eighth wonder of the world which, in its time, was also the most successful tourist attraction on the planet.

That is what it became when it opened in 1843 as the world’s first underwater tunnel. Built by the redoubtable Anglicanised Frenchman Sir Marc Brunel – helped by his son Isambard – it was originally designed to convey horse-driven cargo under the Thames. The aim was to avoid the hassle of having to cross the surface of the river, with thousands of ships sailing along it in both directions each day.

Digging started in 1825 on the Rotherhithe side of the river, but soon ran into horrendous problems of fire, flooding, subsidence and foul air and was closed for seven years.Work started again in 1834 with the help of a loan from the Treasury. Five and a half years later, hugely over budget, it reached the other side of the Thames but it was not opened to the public until 1843.

The tunnel wasn’t wide enough to accommodate vehicles and the builders couldn’t afford the money for the ramps needed for lifting cargo onto trucks, so it began as a tunnel for pedestrians only.

Then came the surprise – an amazing 1.4 million people came to see the eighth wonder of the world in its first four months and two million in the first year, making it the most successful tourist attraction on the planet. Visitors came from around the world to see the first tunnel of its kind, even though the curmudgeonly Victorian essayist Augustus J Hare described it as “this long useless passage under the river”.

The tunnel was built with innovative building techniques involving a slowly advancing rectangular cage, the principle of which has continued to guide the construction of underground tunnels across the world, including the Channel Tunnel and Crossrail.

Miners would dig inside a protective frame, leaving bricklayers to construct a retaining wall as they moved very slowly forward. Incredibly, Marc Brunel based the design on how the shipworm Toredo navalis bores into ships’ timbers by excreting the bored wood and using it to re-inforce the tunnel as it moves along – a marvellous example of engineering mirroring nature.

The project was not without tragic consequences. The tunnel flooded five times. Six men died during the construction and Brunel Junior narrowly escaped with his own life during one of the floods.

In 1865 the East London railway company purchased it, and four years later trains started to run through the tunnel. In those days, the trains were steam-driven with no ventilation shafts, so it cannot have been a relaxing journey.

The tunnel is still there, more or less as it was, and you can journey through it on the train. If you start from the Wapping side of the river you can see the twin Victorian shafts at the end of the platform (photo above).

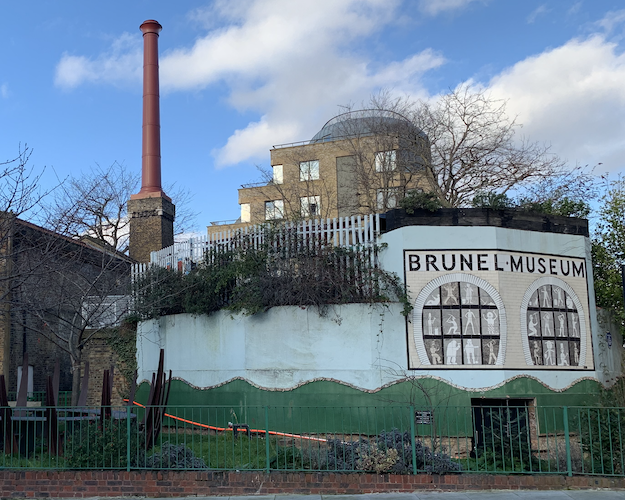

If you go to the nearby Brunel Museum – a must for anyone with an interest in Britain’s industrial history and the genius of the Brunels – you can tread on the floor of the large tunnel entrance shaft, where father and son were often to be seen. This was another Marc Brunel first. He built a large brick tower and allowed it to sink under its own weight, avoiding the need to dig a big hole and line it with bricks. On a side wall there is the original pipe which Thames water was pumped up to prevent the tunnel from flooding. It is still doing the same job today.

The museum is planning a major reconstruction, but it is absolutely worth a visit as it is now in order to get immersed in one of the amazing achievements of the Industrial Revolution. If you have time, walk a little way eastwards along the Thames and you will see the remains of the launching pad of Isambard’s Great Eastern, which was the largest ship in the world at the time and held that record for 40 years. This part of the river should be renamed Brunel-on-Thames.

Photographs by Vic Keegan. All previous instalments of Vic’s Lost London series can be found here.

OnLondon.co.uk is dedicated to improving the standard of coverage of London’s politics, development and culture. It depends on donations from readers. Can you spare £5 (or more) a month? Follow this link if you would like to help. Thank you.