The Royal Panopticon of Science and Art on the eastern side of Leicester Square – where the Odeon cinema now is – was a dramatic, self-confident building in the Moorish style (picture above). It was born of the Victorian ideal of “recreational learning” and completed in 1854, shortly after the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park, and named after Argus Panoptes, an all-seeing multi-eyed giant in Greek mythology. There, for the price of a shilling, visitors could enjoy scientific exhibitions, lectures, fountains, demonstrations of electricity, a vast panorama and a host of other delights.

Alas, although it attracted over a thousand visitors a day, the Royal Panopticon only lasted two years before being auctioned off. It fared better than an earlier and more notorious building based on similar design principles, which never got off the ground. It did, though, have ominous repercussions which are still with us today.

A panopticon is an expression of a concept of human discipline. When utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham drew up plans for a new National Penitentiary at Millbank beside the Thames in Westminster, his idea – or, more precisely, his brother Samuel’s – was to build it as a panopticon. The lay out was intended to enable a single guard at the centre to supervise every convict in their cell without the convicts knowing what was going on. Bentham described it as a “new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in quantity hitherto without example”.

As critics have not been slow to point out, the concept has been adopted both in fiction (George Orwell’s 1984) and in real life, as with the Chinese authorities’ policy of surveying the lives of citizens remotely in real time, using digital technology. We experience some of the effects in Britain, where networks of CCTV security cameras enable one person to monitor what’s going on all around a building or a network of streets or stations.

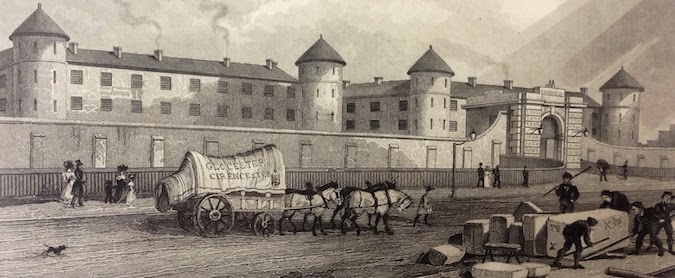

A Millbank Penitentiary, which looked a bit like a Panopticon from above, was eventually constructed (image above). It went through many phases – including being a staging post for prisoners being exiled to the colonies – but as an experiment in prison reform it was a failure. It was eventually demolished, but the bricks found a good home as part of the admirable Millbank housing estate behind it. And the site itself found an even better future when the Tate Gallery – now Tate Britain – was built in its place. Maybe we should view it as a Panopticon of British Art.

All previous instalments of Vic Keegan’s Lost London can be found here.

OnLondon.co.uk exists to provide fair and thorough coverage of the UK capital’s politics, development and culture. It depends greatly on donations from readers. Give £5 a month or £50 a year and you will receive the On London Extra Thursday email, which rounds up London news, views and information from a wide range of sources. Click here to donate directly or contact davehillonlondon@gmail.com for bank account details. Thanks.

Fidel Castro spent time as a political prisoner in Cuba’s Panopticon Prison. He described it as the University of revolution. The guard in the centre could see the well-behaved prisoners, but not what they were reading in their cells or saying to those in the adjacent cells, while not seeming to talk to them

Fascinating. Thanks