The structure pictured above was one of the most unusual monuments in Victorian London. It looks like a Hawksmoor steeple gone wrong. In fact, it is a 20-yard high tower with a police station at the bottom (later upgraded into a pub) a camera obscura somewhere high up, a clock and, at the very top, an 11-foot high statue of George IV, who didn’t live to see its completion.

The column was built in 1830 in an attempt to raise the tone of the neighbourhood as part of a grand but short-lived entertainment complex called the Panharmonium. It graced the intersection where today’s Euston, Pentonville and Grays Inn roads meet, but didn’t last very long: the statue of George was pulled down in 1842 and the rest went a few years later to ease traffic flow. However, its name became firmly attached to the junction where it stood and to the wider area – King’s Cross.

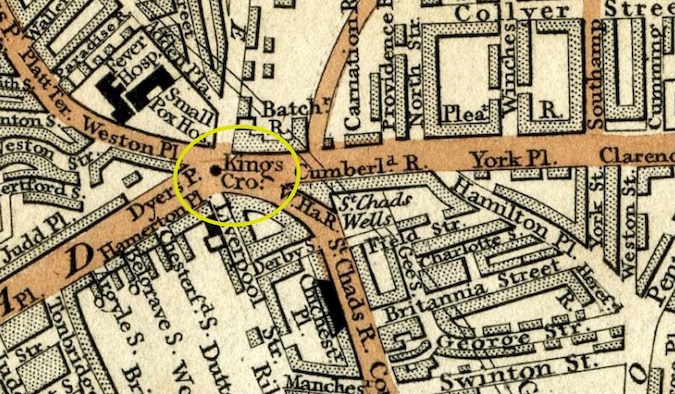

This was despite George not being a hit with the public and the King’s Cross building being dismissed by author Walter Thornbury as “a ridiculous octagonal structure crowned by an absurd statue”. Its name soon appeared on maps (see below), prevailing over the area’s former one of “Battle Bridge”, which derived from a crossing over the River Fleet, since covered in, where a battle was popularly believed to have taken place between the Romans and Britons under Queen Boudica (If only).

Recently, there have been moves to put the King back into King’s Cross, so far to no avail. Billions of pounds have gone into the King’s Cross redevelopment, and a revival of the statue of the monarch who gave it its name would have added only a small extra cost.

A simple solution may be at hand, though. There is a little noticed bronze statue of George IV on horseback at the north-east end of Trafalgar Square. It was originally intended to go on the top of the Marble Arch, at the time when the arch itself was going to be positioned outside Buckingham Palace. Instead, if you’re still with me, the statue was plonked on its Trafalgar Square plinth as a temporary resting place and has been there ever since.

It makes sense for there to be a model of George IV at King’s Cross, even though he wasn’t a model king. George IV’s reign saw some achievements, but few of them were down to George himself, who was profligate in his official and private lives. For example, he ejected his wife from his coronation at Westminster Abbey as he had by then become besotted with one of his numerous mistresses. Kings will be kings.

All previous instalments of Vic Keegan’s Lost London can be found here and a book containing many of them can be bought here. Follow Vic on Twitter.

On London strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. Become a supporter for £5 a month or £50 a year and receive an action-packed weekly newsletter and free entry to online events. Details here.