In 1887 Queen Victoria, in the first official engagement of her Jubilee year, opened a building in the East End of London. It was called The People’s Palace and was designed to bring “intellectual improvement and rational recreation” to a deprived area of London.

The rich already had their entertainment outlets with such spectacular playgrounds as Vauxhall Gardens and, later, Ranelagh Gardens. These had pricing policies designed to keep out the working and lower middle classes. The People’s Palace in the Mile End Road was, like its counterpart Alexander Palace, intended to right this wrong.

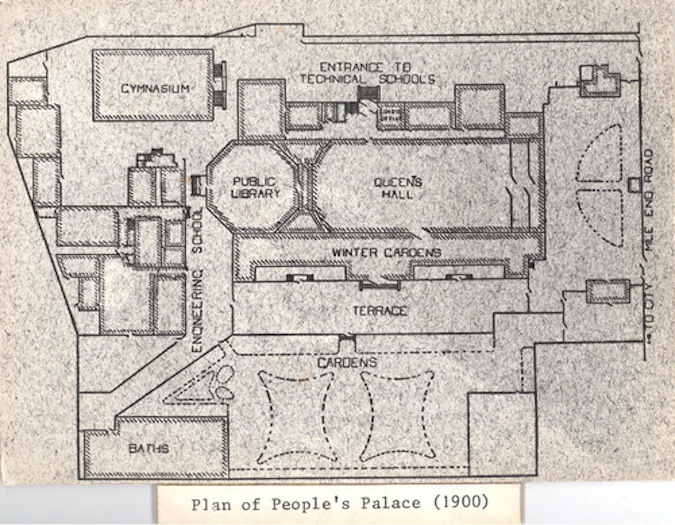

Built on the site of Bancroft’s School and Almshouses on land bought from the Draper’s Company, one of the City of London’s ancient livery companies, its central feature was the huge Queen’s Hall (see above), a concert venue named in Victoria’s honour. It could accommodate 4,000 people and was described by the Times as a “happy experiment in practical socialism”.

The complex also contained an octagonal library of 250,000 books – inspired by the reading room of the British Museum – a glass-enclosed Winter Garden, a gym, gardens and baths. The Draper’s Company also established two technical schools, known as the People’s Palace Institute, adjacent to the Palace itself. These opened in October 1888 and provided much needed day and evening classes in technical and practical skills ranging from tailoring to carpentry and needlework.

It was built with the help of money from philanthropists such as businessman Sir Edmund Hay Currie, public donations and the unstinting generosity of the Draper’s Company. But the idea for it came from a remarkable man and an unusual source – Walter Besant, who is barely known today except to enthusiastic historians of London.

Besant wrote a number of detailed books about different areas of London and was an important force behind the monumental Survey of London. He also wrote, or in some instances co-wrote, over 40 novels. Some at the time ranked only George Meredith and Thomas Hardy above Besant as contemporary novelists.

One of Besant’s novels is regarded as the first of a new genre of “slum fiction”. It was called All Sorts and Conditions of Men and sold over 250,000 copies. In it, Besant imagined a “palace of delights” of education and entertainment for the working classes of the East End. This was the origin of the People’s Palace.

It was intended to remedy a situation in which the two million or so working class east Londoners had, in Besant’s words, “no institutions of their own to speak of, no public buildings of any importance, no municipality, no gentry, no carriages, no soldiers, no picture galleries, no theatres, no opera — they have nothing”.

The Peoples’ Palace proved enormously popular, receiving 26,000 visitors on a single bank holiday and 1.5 million in its first year. The two technical schools, where a range of subjects including engineering and physics were taught, became the East London Technical College, then East London College and then, in 1916, Queen Mary College, the queen being Mary of Teck, wife of King George V. These successes were, as the lawyer Sir Lynden Macassey wrote in the Times, a “striking refutation of all the early critics, who thought that university education was an unnecessary luxury for east London”.

All went well with The Peoples’ Palace until 1931 when the Queen’s Hall burned down. This, bizarrely, echoed a similar fate that had caused extensive damage to Alexandra Palace – also known as a “People’s Palace” – soon after it opened and the Crystal Palace after it had moved to Sydenham. All that was left was the frontage of the building.

However, the library survived and with the rest of the palace came under the sole use of the college, which in 1934 was given a royal charter and became Queen Mary University. The library is now the university’s Octagon venue, available for banquets, conferences and receptions. A new hall, the Great Hall, though also known as a new Peoples’ Palace, was built and opened by George VI in February 1937. It too still stands today.

Walter Besant was a bit of a university in his own right. In addition to his novels and voluminous works on London he wrote biographies of the philosopher Michel de Montaigne, Francois Rabelais and French humourists from the twelfth to the nineteenth century. In 1884 he founded the Society of Authors, the first serious organisation to campaign for the protection of literary rights for writers in the United Kingdom. Some of his prolific output is listed here.

Besant’s fame faded after his death, but Queen Mary University of London is his epitaph. A small seed planted by him grew and grew to become an international educational institution and a member of the prestigious Russell Group of universities while remaining rooted in the East End. And it all sprang from the pages of a novel, a fairy story come true.

All previous instalments of Vic Keegan’s Lost London can be found here and a book containing many of them can be bought here. Follow Vic on Twitter.

On London strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. Become a supporter for £5 a month or £50 a year and receive an action-packed weekly newsletter and free entry to online events. Details here.